Pitch Perfect?

Experienced showrunners weigh in on how to nail that first pitch meeting — and how to keep the faith if it all goes pear-shaped

By Diane Wild

Brad Wright’s worst pitch experience was also his most successful. Not long into his pitch for Stargate-SG1 to the head of Showtime, the fire alarm went off, and Wright found himself continuing to make his case in the parking garage with the building’s evacuated occupants milling around. “I don’t remember much of what I said, but when the alarm stopped, he told me I didn’t have to come back up. It turned into a 44-episode order.”

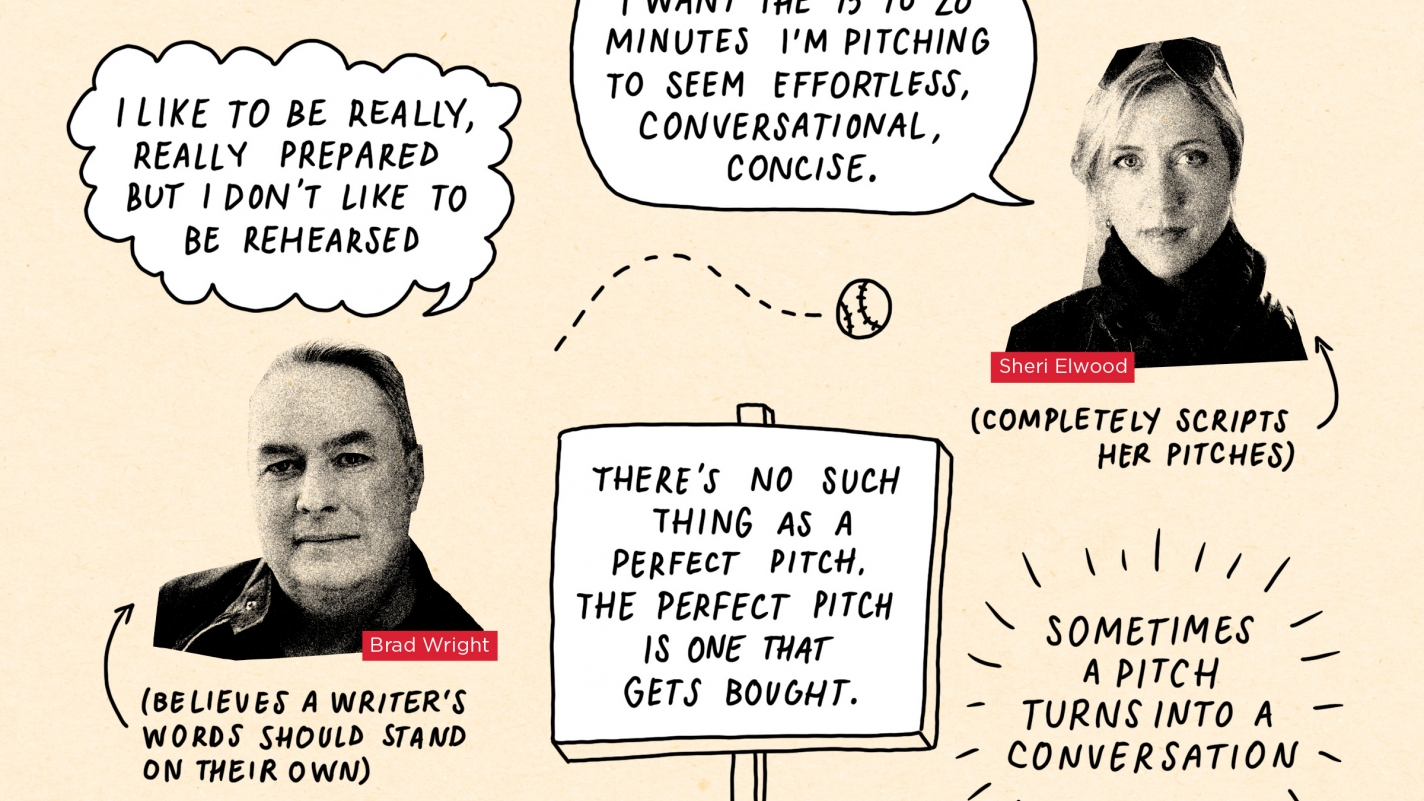

“There’s no such thing as a perfect pitch,” he says. “The perfect pitch is one that gets bought.”

From writing and memorizing a verbatim pitch script to being prepared enough to improvise in the room, there are as many ways for writers to pitch their series concepts as there are personalities in a writers’ room.

“As long as you love the story you’re pitching, you’ll be fine,” Dennis Heaton says. “You need to be passionate about the story, because that creates an energy in the pitch.”

Conversely, Sheri Elwood completely scripts her pitches, down to every joke and pause, because “I’m not a great performer.” Even then, “I want the 15 to 20 minutes I’m pitching to seem effortless, conversational, concise. I’ve put in two months crafting the pitch then getting off book. It can be fun once you know your own material — you have space to riff in the room.”

“Read the room,” says Sarah Dodd. “Sometimes a pitch turns into a conversation. You don’t want to be ‘stuck on send.’ If your audience wants you to stop, listen and discuss, then go with the flow. You don’t always need to hold fast to the pre-rehearsed pitch you prepared.”

“I like to be really, really prepared, but I don’t like to be rehearsed,” Wright says. “You want them to want to be in business with you as a person, as well as your idea. I think that’s what a lot of people get wrong — being too rehearsed and not being themselves enough for the buyers to know who they’re working with.”

Structuring the pitch

Wright often writes the script first, and even sends it before the pitch meeting. “To understand my characters, I need to write them, to give them dialogue, have them interact. I learn more about my characters in the writing process than anything else.”

Heaton also prefers to write the full story. “Either a full script or an outline or even just an expanded episode pitch,” he says. “Just so I can make sure the concept will actually result in a full story.” After that, he writes a five- to seven-page pitch document, a five-page verbal pitch script, and lastly a logline.

“A verbal pitch always starts with an explanation of an idea’s genesis and why it’s important to me,” says Heaton. “Then I give the logline and then launch into the pilot story, describing the characters as I introduce them in the story. I end the pitch when I get to the end of the story and get back to a conversation as quickly as possible.”

A Netflix executive once told Dodd that Canadians are the only writers on the planet who lead with place, which she does not advise. “Instead, think about the global audience and why this story has themes that will resonate with the largest possible audience.” She starts with her own connection to the material, the premise, and painting a picture of where the story begins.

“It’s challenging sometimes for a writer not to fall into a laundry list of plot points,” says Dodd. “After a really cinematic introduction, it’s time to focus on a broader middle and end to the pilot, teasing the listener with a few juicy twists and turns and emotional moments.” She then moves on to the first season’s broad strokes and an indication of the story engine for seasons to come.

“The most important thing is making the pitch personal,” Elwood says. “I like to start with an anecdote about what inspired me to write it, why I was drawn to the material. There are only so many original ideas, but what makes it special is the lens you filter it through.”

Call Me Fitz, for example, was loosely based on her brother, a car salesman. “I was out to lunch with my grandmother back in his playboy days and she said, ‘That boy needs to have a stiff drink with his conscience.’ It became a buddy comedy about a car salesman and his conscience.”

Elwood organizes her pitches into an introductory anecdote about why she relates to the material, what the concept is, and then she rolls into the location and core characters. “For a drama, I often pitch the whole cold open,” she says. “I give a rough flow of season one, even if it’s ‘We’ll begin with X and at the end of the season we’ll find out Y.’ For comedy, I’ll set up episode ideas, just one line each. ‘This is the one where Fitz turns the local daycare into a brothel.’ For a drama, I might give character arcs instead.” After about 20 minutes of specificity, she wraps up by bringing her pitch around to why the concept is universal, relatable and compelling.

“Never leave materials [printed or otherwise] behind,” Elwood cautions. “You’re a writer: Those are your words, and there’s a monetary value to that. Leave the pitch in the ether and leave them wanting more. And if they want more, they can buy it.”

Judicious use of props

“I usually bring visuals,” says Elwood. “I might show actors to give the tone of a character. I might bring location photos to give a flavour of the setting. I bring an iPad to flip through the photos, and that’s a good job for the non-writing producer.” For Bagel Nation, she came with bagels and cream cheese. For an L.A. Story adaptation, she brought a cartoon map of L.A. with character faces stuck on particular locations.

Wright has paid for graphics to be created by a production designer in order to convey an idea, though he believes a writer’s words should stand on their own. “If you’re good at your job, the words you’re saying are going to paint pictures in their mind — possibly better imagery than you can afford at the pitch stage.”

“I think some form of visual proof of concept is great,” says Heaton. “But it should be shown either before as an amuse-bouche to get the room excited, or after a pitch to prove that the crazy idea you’ve just pitched can actually be pulled off.”

Keep the faith

“I’ve had pitches that I didn’t think went well not get bought and pitches I thought were home runs that didn’t get sold,” says Wright. “Sometimes you did a great job, the people in the room wanted to buy it, but they went down the hall and the boss said, ‘Meh.’”

“I really had to learn how to be a successful pitcher,” says Elwood. “In the early days, I’d have my crunched-up pages with my notes. You don’t ever want to be reading from a script.”

“Before one meeting I took a Xanax and almost fell asleep during my own pitch. That’s frowned on,” she laughs. “It should be noted that I did not sell the Xanax pitch, but I have used that scene in another show. Self-humiliation is an excellent selling feature.”